+86 13816508465

Pump Knowledge

Feb. 09, 2026

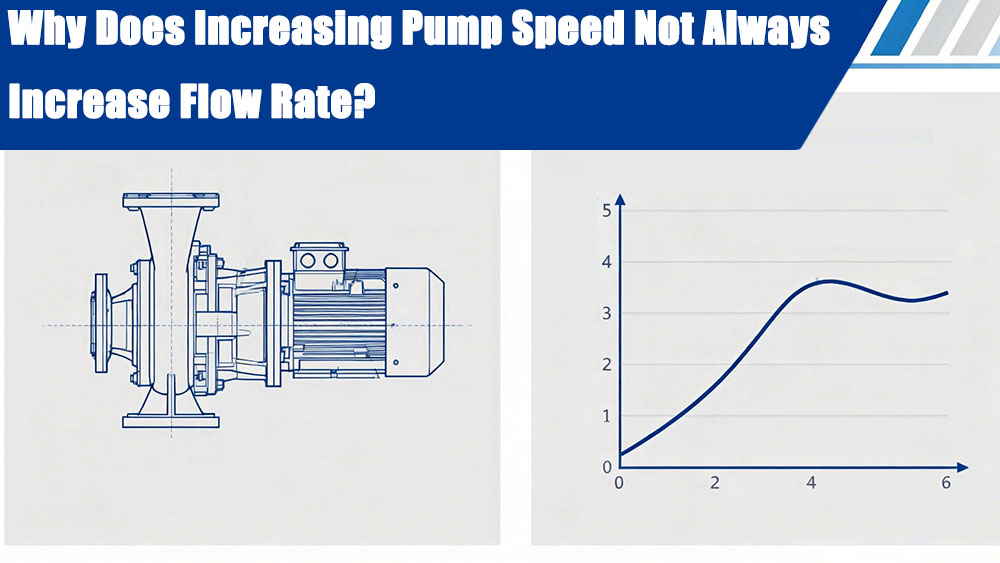

If you have a centrifugal pump that isn't delivering enough water, the most intuitive solution seems to be: [Speed it up.] Whether you are tweaking a Variable Frequency Drive (VFD) or swapping out a motor, the assumption is simple. If the pump spins faster, the flow rate must go up.

Unfortunately, in the real world of hydraulics, this assumption frequently fails.

While increasing rotational speed usually increases pressure, it does not guarantee a proportional increase in flow. For engineers, buyers, and system designers, this counterintuitive reality can lead to wasted energy, damaged equipment, and costly downtime. This article explains why [more RPM] doesn't always equal [more flow] and explores the hidden hydraulic limits that dictate actual performance.

To understand why things go wrong, we first need to look at how they are supposed to work in theory. The Pump Affinity Laws provide the mathematical baseline for centrifugal pump performance.

According to these laws, flow is directly proportional to speed:

Flow (Q) ∝ Speed (N)

If you double the speed, you theoretically double the flow. However, this rule comes with a massive asterisk. It only holds true if:

The impeller diameter remains constant.

The fluid viscosity and density are unchanged.

Crucially: The system resistance remains constant.

In a vacuum or a perfectly linear friction-only system, the Affinity Laws are accurate. But industrial piping systems are rarely perfect or linear. This theoretical baseline is a starting point, not a guarantee.

The pump is only half the equation. The other half is the system it pumps into.

The System Curve represents the resistance the pump must overcome to move fluid. It is composed of static head (elevation) and friction head (drag in pipes).

When you increase the pump speed, you are shifting the Pump Curve upward and to the right. You are not changing the System Curve. The actual flow rate is determined by the intersection point of these two curves.

If your system curve is extremely steep—meaning a small increase in flow creates a massive increase in resistance—speeding up the pump will yield very little extra flow. The pump will simply push harder (more pressure) against a wall of resistance that refuses to budge.

When you hit the [speed up] button on a VFD, you aren't just affecting flow. You are affecting head (pressure) even more aggressively.

The Affinity Laws state:

Flow changes with speed.

Head changes with the square of the speed ().

This means that as you speed up, the pump becomes much better at generating pressure than it does at generating flow.

In systems with high static head (e.g., pumping water up 20 stories), the pump spends most of its energy just overcoming gravity. If you increase speed, you might see a spike in discharge pressure, but because the pipe friction also fights back, the actual volume of liquid moving through the pipe may barely change. You are essentially pressurizing the line without moving much more product.

Physics works against you when you try to force more fluid through a fixed pipe diameter.

Friction losses in pipes, valves, and elbows do not increase linearly. They increase roughly with the square of the flow rate.

If you try to double the flow, you create four times the friction.

As you increase pump speed to get more flow, the system pushes back exponentially harder. Eventually, the energy from the increased speed is entirely "consumed" by the friction losses of the piping. The pump is working much harder, and the pressure at the discharge is higher, but the flow rate flattens out because the pipe simply cannot accept more fluid without a massive, inefficient waste of energy.

Speed has a dangerous side effect: it changes the suction requirements of the pump.

Every pump has a required Net Positive Suction Head (NPSHr) to prevent cavitation. As pump speed increases, the NPSHr increases significantly (often by the square of the speed change).

If your available suction pressure (NPSHa) stays the same while the pump's requirement shoots up, you cross a dangerous line. The pump begins to cavitate—forming vapor bubbles that collapse destructively.

The result: Cavitation blocks the flow path with vapor pockets.

The symptom: You increase RPM, but flow actually decreases or becomes unstable, accompanied by the sound of gravel rattling in the casing.

Pumps are designed to operate at a Best Efficiency Point (BEP). When you drastically change the speed, you often shift the operating point away from this sweet spot.

If increasing speed pushes the pump too far to the right of its curve (into high flow territory), efficiency plummets. Instead of moving water, the energy is dissipated as heat and vibration.

Internal recirculation can also occur if the back-pressure is too high. The fluid spins around inside the casing rather than exiting the discharge, meaning the flow rate at the outlet doesn't reflect the impeller speed.

Even if the hydraulics allow for more flow, the electrical system might not.

Recall the third Affinity Law:

Power (P) ∝ Speed (N)³

Power demand grows with the cube of the speed. A 10% increase in speed requires 33% more horsepower. A 20% increase requires nearly 75% more power.

Often, a VFD will have a current limit programmed to protect the motor. You might command the drive to go to 60Hz, but if the motor hits its amperage limit at 52Hz, the VFD will hold the speed there. You think you've increased the speed, but the controller is electronically restricting it to prevent the motor from burning out.

Sometimes the barrier is artificial. Many modern systems use complex control logic.

Pressure-Based Control: If a booster set is programmed to maintain 100 psi, and you manually increase the speed of one pump, the system logic might simply close a control valve or slow down other pumps to maintain that 100 psi setpoint.

Throttling Valves: If a discharge valve is partially closed to balance the system, speeding up the pump just creates a larger pressure drop across that valve. The valve acts as a bottleneck, ensuring flow stays constant regardless of pump effort.

To visualize this, let's look at three common scenarios where speed fails to deliver flow:

High-Static Lift: A mine dewatering pump must lift water 500 feet vertically. The pump is sped up by 10%. The discharge pressure rises, but because the pipe diameter is small and the vertical lift is the dominant force, the flow increases by only 1-2%, while power consumption skyrockets.

HVAC Circulation: A chilled water pump is sped up, but the 2-way control valves at the air handlers are closing because the building is already cool. The pump spins faster, dead-heading against closed valves. Zero flow increase occurs.

Pressure Booster: A facility manager wants to fill a tank faster and increases the VFD speed. However, the supply line feeding the pump is too small. The pump starves for water (cavitation), and flow becomes erratic and drops, despite the higher RPM.

For engineers and buyers, avoiding these pitfalls is key to smart selection:

Myth: More RPM always means more flow.

Reality: More RPM always means more capability, but the system decides if that capability becomes flow or pressure.

Myth: The pump isn't working; we need a bigger one.

Reality: Often, the piping is the bottleneck. A bigger pump will just waste more energy.

Error: Ignoring the system curve.

Fix: Always overlay the new pump speed curve onto the system curve to see where the actual operating point lands.

Before reaching for the speed dial, follow these steps:

Check the System Curve: Is your system friction-dominated or static-head dominated? Friction systems respond better to speed changes than high-static systems.

Evaluate Suction Conditions: Calculate the new NPSHr at the higher speed. Do you have enough margin?

Impeller Trimming vs. Speed: Sometimes, a larger impeller running at a slower speed is more efficient than a small impeller running fast.

Look at the Pipe: If the velocity in the pipe exceeds 10-15 ft/sec, increasing pump speed is futile. You need larger pipes, not a faster pump.

Flow rate is a negotiation between the pump and the system. The pump proposes a flow based on its speed, but the system accepts or rejects it based on friction and pressure.

Increasing pump speed is a powerful tool, but it is not a magic wand. It primarily adds pressure (head), which may or may not translate into flow depending on your piping, valves, and suction conditions. Correct pump selection requires analyzing the entire hydraulic loop, not just the RPM gauge.

Does a VFD always increase flow?

No. A VFD controls motor speed. Whether that speed translates to flow depends on the system resistance. In some cases, increasing frequency on a VFD will trip the motor on overload before significant flow gains are realized.

Can a bigger motor solve the problem?

Only if the previous motor was the limiting factor (tripping on overload). If the limitation is hydraulic (pipe friction or cavitation), a bigger motor will just consume more electricity without delivering more fluid.

How much speed increase is safe for centrifugal pumps?

Generally, you should not exceed the manufacturer's maximum rated speed. Going beyond this risks shaft deflection, bearing failure, and catastrophic impeller explosion due to centrifugal forces. Always consult the pump curve and data sheet.

Address

No.17 XeDa Jimei Ind. Park, Xiqing Economic Development Area, Tianjin, China

Telephone

+86 13816508465

QUICK LINKS